Iran. Isfahan, the city of dancing minarets

[Article originally published on December 2, 2004] “Esfahan nesf-e djahan” (“Isfahan is half the world”). Obviously, the author of this pun knew what he was talking about. Located right in the middle of the vast Iranian desert, the city is unquestionably one of the jewels of Persian Islam: it is a veritable architectural symphony born from the fusion of the best of Islamic and Persian aesthetic traditions.

Markets, mullahs, mosques…

For all those, like me, whose childhood was rocked by the tales of Hadji Baba [The Adventures of Hadji Baba of Isfahan (1824), by James Morrier, an oriental tale which relates the tribulations of a Persian barber] , the mere mention of Isfahan conjures up a host of images: markets teeming with activity and overflowing with oriental products of all kinds, mullahs hurrying through the maze of alleys, splendid mosques and minarets, vast gardens at every corner. of street.

Today's Isfahan is all of this and more. It is a modern city with wide arteries, connected to other major Iranian cities by plane, train and bus, and where one of the most modern universities is located. If you go looking for your Hadji Baba, you may even find him.

But you will also meet elegantly dressed men and women strolling through the city. Isfahan mixes the old and the new in perfect harmony. The horse-drawn carriages dear to tourists make their way between large cars and motorcycles; countless souvenir shops, where kitsch objects and Persian crafts are lined up, compete for the favors of visitors.

Golden age

Isfahan lies at the foot of the Zagros Mountains range, 400 kilometers south of Tehran. Built on the banks of the Zayandeh Roud, the third largest city in Iran appeared two thousand seven hundred years ago, when a Jewish colony settled in the region. In the middle of the 7th century, the Arabs made it their provincial capital, then Ispahan became the capital of the Seljuks, a people of Turkish origin, in the 11th century. Tamerlane, a sovereign from Central Asia, seized the city in 1388 and ransacked it, but his reign also left the architecture of Ispahan strongly marked by Mongol influence.

It was in the 17th century that the city experienced its golden age: Shah Abbas the Great, Safavid sovereign, abandoned his capital, Qazvin, to build in Isfahan a city of unparalleled beauty and sumptuousness. In fact, Islamic architecture reaches heights of extravagance in the many minarets, mosques and madrasas [Koranic schools] that dot the city. Ispahan is, like Rome or Saint-Petersburg, a gigantic museum and it owes most of its monuments to the Safavids.

In Isfahan, all roads lead to Naqch-e Djahan, certainly the trendiest place in the old city – since its creation four hundred years ago. The inhabitants of the city as well as the tourists come there in droves, especially in the evening, giving the place a carnival air throughout the tourist season.

In the center of Naqch-e Djahan, Meidan Emam is arguably one of the largest squares in the world, larger, according to locals, than Red Square in Moscow or St. Mark's Square in Venice. The Meidan Emam is a quadrangle 500 meters long, covered with an emerald green lawn dotted with fountains, flowerbeds and shrubs, overlooked on two sides by sumptuous mosques with sparkling domes, and on a third, a palace.

Young girls stroll, children play ball

The fourth side of the square overlooks the bazaar, a must in this part of the world. An avenue borders the square; on three of its sides, it is reserved for pedestrians and, of course, for elegant carriages intended for tourists wishing to embark on a time machine.

This is where I station myself to observe the peaceful unfolding of local activities. Young girls kill time by strolling, others are seated on the edge of the fountains; children play ball. The tourists, on the other hand, do what they do best – haggle with vendors or, like me, frantically photograph everything in the hope of bringing home some of this beauty.

Of the many domes, none is more dazzling than that of the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, with its brown and gold cupola and breathtaking blue facade. There is no doubt that this jewel of Isfahan is one of the most refined testimonies of Safavid art.

Built by Shah Abbas in 1619, and named after a highly respected Muslim thinker from present-day Lebanon who was the director of a theological school in Isfahan, the Lotfollah Mosque occupies the western side of Naqch- e Djahan and overlooks the square. Its arched portal, richly decorated with arabesque stalactites and a yellow and blue mosaic, opens onto a dark gallery giving the visitor the impression of entering some mysterious alcove. It takes you to the holy of holies, to the very heart of this perfectly proportioned dome.

exuberant splendor

The Lotfollah mosque does not use artificial lighting: up there, at the base of the dome, sixteen latticework windows, also arched, let in a soft light that accentuates the imposing and mysterious character of the place. It is only once accustomed to this dim lighting that the visitor can discover the exuberant splendor of the mosque. The mosaics adorning the interior of the vault reveal an incredible richness of designs and colors. The glazed ceramic blue-green background beautifully showcases blue and gold geometric and floral patterns.

As in all mosques, the part of the building facing Mecca is decorated with particular care. The ceiling itself is a true chromatic symphony, with its lotus flowers arranged in a crescendo, from the periphery to the centre. No wonder the Lotfollah Mosque is a popular site for art students, mostly young women. Isfahan is also, in the purest oriental style, a gigantic bazaar.

In addition to the covered market, stalls are omnipresent in Naqch-e Djahan, under stretched canvases to hide the sun. Street vendors offer all kinds of products – carpets and kilims, but also embossed copper dishes and clocks with intricate decorations, inlaid with gold or small mirrors. A real treat for the window-shopping enthusiast. I then go to the Emam mosque. I wear the veil, like the women of Isfahan, and the counter clerk, believing me to be Iranian, hands me a ticket, addressing me in Persian. But when I answer him in English, he quickly takes it back and pulls out a notebook reserved for foreign visitors.

As in most tourist sites in the world, visits to monuments are subject to two different prices, and the price for foreigners is quite high. My wanderings from one Iranian site to another seriously lightened my wallet, but I got what I paid for.

I feel very small

The Emam Mosque, which also bears the name of Masjed-e Shah [King's Mosque], is a real architectural fantasy built at the beginning of the 17th century. Its outer courtyard, which bears a striking resemblance to that of the site of Humayun's tomb in Delhi, leaves me with a feeling of deja vu. Under its huge portals, I feel very small, crushed by the incredible height of the vaults. With its 51 meters high, the dome of the mosque is the highest point in Isfahan. The building is emblematic of the Seljuk period, with its four iwans [barrel-vaulted ceremonial room open in front over its entire height] all leading to a large domed room, and the two floors of pointed arcades which border it. Every square centimeter is adorned with floral motifs, the intricate interlacing of which produces a kaleidoscopic effect.

The smallest surface, whether it be brick, covered with mortar or lime, is covered with small tiles – there would be, it is said, more than 400,000. n the dazzle caused by so much splendor and color in a single day, the main dome of the Emam mosque is under construction: horrible scaffolding disfigures its sumptuous blue facades. The site also includes two vast courtyards, one of which houses an immense square basin in which are reflected panels, porticoes and minarets. Noisy Iranian schoolchildren visit the Emam mosque at the same time as me, stopping in front of the smallest archway to have their picture taken.

Like the VIP stand of a stadium

It is with regret that I leave the mosque to head towards the Ali Ghapu palace. At first glance, it looks more like a pavilion than a palace. Yet it is one of the many residences of Shah Abbas, located on the eastern side of the square, opposite the Lotfollah mosque. There was even a secret underground passage that allowed the women of the harem to go from the palace to the mosque without being seen. But unfortunately for me, Ali Ghapu is also under construction. The visitor is however allowed to go up to the gallery located on the sixth and last floor to admire the view. It is reached by a steep, narrow and dark staircase, in a strong smell of bat droppings.

Overlooking the square, the gallery resembles the VIP stand of a stadium. I will learn later that this place was actually intended to host the Safavid royal family during polo matches. The neat lawn of Meidan Emam Square would therefore have been a polo field in the past. The music room, with its elaborate motifs – vases, flowers and birds – cut into the plaster, is the most striking place in the palace. The ceiling of the gallery, decorated with paintings, is supported by eighteen columns encrusted with small mirrors. Made using natural tints, the paintings are in perfect condition.

I then stroll through the pretty gardens and find myself near another palace, not far from Naqch-e Djahan. Octagonal in shape, Hacht Behecht (the Palace of the Eight Heavens) was designed so that the gardens could be seen from anywhere in the palace. Thanks to inventive mirror inlays, the roof of the building seems to float in the air; the setting sun gives the palace a magical charm. Not far from there is also the Tchahar-Bagh madrasa, surrounded by a peaceful and shaded garden. Back in Emam Square, I decide to explore the covered market. Nothing like this bazaar, with its arched vaults and its multitude of local products, to take a real trip back in time.

Resist the Persuasion of Merchants

Illuminated by natural light alone, the market bustles with activity. The essential kilims and other Persian rugs are hung from all the arcades, alongside shawls whose fabric is beautifully worked. The black chadors, suspended from the ceiling, have something disturbing about them. A zealous salesman is on the prowl behind every arcade, ready to convince you to buy his superb merchandise. It's not that tourists need to be pushed, or that they take a dim view of the talent of merchants, but on my side, with my tight budget, I have to show an unwavering will to resist their powers of persuasion.

But no sooner have I got rid of a particularly insistent vendor than another stalks me to make me taste his dried fruit. His stall is full of delicious fruit, pistachios from Rafsanjan [region of southeastern Iran], figs, plums and dried apricots that he hands me handfuls. Impossible to resist. My will melts like apricots under my palate, and it is loaded with two kilos of dried fruit that I continue my wanderings in Isfahan that evening. If the mosques, minarets and madrasas with sumptuous decorations are commonplace in the Muslim world, it is its magnificent bridges spanning the Zayandeh Roud that make Isfahan a unique place.

The thirty-three arches of Si-o-Seh Pol

That evening, the last monument I will admire is the Si-o-Seh Pol, a bridge of thirty-three arches which is the most photographed building in Isfahan. It is again to Shah Abbas that we owe this marvel of architecture. From each end of the bridge, the visitor can admire a row of arcades whose harmonious design continues to the opposite bank. It's Thursday evening, and since Friday isn't worked, the banks of the river are black with people. Located under an archway of the bridge, the tchai-khana [tea room] has everything of a museum, its walls disappearing behind a multitude of ancient knick-knacks. I learn that the place is a compulsory passage for visitors, but it is also a popular place for the inhabitants of Isfahan for its green tea and its hookahs. Night falls little by little on the city and, under the artificial lighting, the bridge takes on a festive air. The next morning, I get up early and take the direction of the Khadju bridge, of which I have heard so much saw some great pictures on the internet. In truth, the Khadju bridge is magnificent. The fact that a simple bridge has been the subject of such attention to detail is an eminent testimony to the aesthetic sense of the Safavids. With its two levels of arcades with crossed arches and, in the centre, two pavilions with sumptuous ornamentation, the bridge is a model of balance and harmony. The foam of the water cascading down the stone steps of the building gives it a vaporous and unreal appearance. The bridge and the banks of the river are traversed by many morning runners, to whom the extraordinary beauty of the city seems to be neither hot nor cold. I hail a cab and drive to the Fire Temple on the outskirts of town.

Head to the trembling minarets

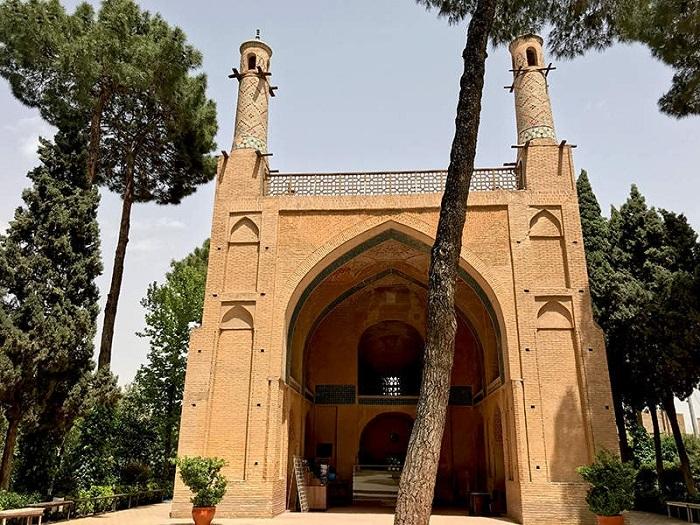

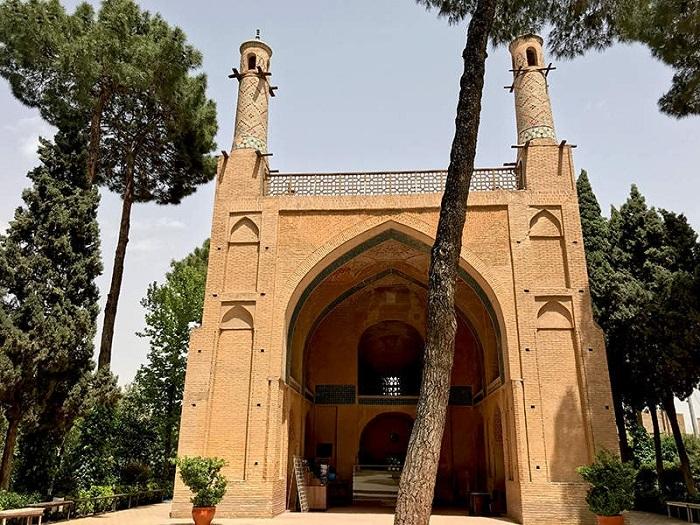

The monument is located at the top of a rocky mound and there are no stairs. The sun is high in the sky, I'm already sweating. The sides of the hill look slippery and it probably takes an hour to reach the top. The sight of an entire family, on all fours, descending the mound as best they could seriously undermined my determination. After a few moments of hesitation, I turn around and settle for a simple photograph of myself in front of the landscape, taken by my friendly driver. From the bottom of the hill, I can see the ruined walls of what once must have been a Persian temple. Here we are on our way to the Minar-e Djonban, the trembling minarets. At first glance, the whole complex is rather small and unremarkable, although decorated with the same attention to detail as any other monument in Isfahan. A crowd of tourists is massed in front of the building and does not take their eyes off it.

It was then that a man took the spiral staircase leading to the top of one of the minarets and set it in motion. And there, believe me if you want, the minaret literally begins to shake, then to sway like a palm tree in the storm. A few moments later, a second minaret joins the first, as if in a movement of empathy. Two minarets, therefore, sway together in front of captivated spectators. But the man comes down from the tower: voices then rise in chorus, begging him to start again, and, with an indulgent smile, he complies. His job is to shake the minarets every hour to entertain tourists.

Several stories circulate about the trembling minarets; it is said in particular that the feldspar used would have melted, leaving a void in the foundations of the building which would allow the minarets to swing. But regardless of the scientific explanation of the phenomenon: the spectacle is striking. I am about to conclude my visit to Isfahan to take the bus to Tehran, but my driver insists that I see Djame Masjed, the oldest mosque in the city, which is believed to have been erected a thousand years ago. years on the ruins of a Zoroastrian temple. Djame Masjed reminds me of the Jama Masjid in Delhi. Like the latter, it is located in a very crowded area and surrounded by stalls selling cheap clothes, incense and the like.

We make our way through the swarming crowd in the aisles and enter the mosque through a very ordinary entrance. The interior leaves the visitor dumb with admiration: the arches, columns and portals of perfect proportions and refined decoration, arranged symmetrically, are of absolute beauty. In the center, beautifully decorated shrines line a vast quadrangle bathed in light. Each of the sanctuaries opens onto a vaulted room, huge and cool, covered with carpets, ready to welcome Friday prayers. So I end up getting on the bus for Tehran, but I promise myself to come back. Isfahan is such an architectural delight that a single stay is not enough to appreciate all its flavors.

Sudha Mahalingam- Prev

- Next